I just discovered that my high school gym – one of the coolest gyms I ever encountered in my four years of playing basketball and all the years since then – was a WPA building project. The Works Progress Administration was a major part of the New Deal – FDR’s answer to the massive unemployment of the Great Depression – and I have so much respect for the infrastructure that was built during The New Deal years. I discovered the provenance of Placer High School’s Art Deco-style gym on a fantastic website called The Living New Deal, a project which has been in existence for decades, and has grown into an interactive learning and teaching site devoted to the history and legacy of the WPA. I went down multiple rabbit holes on the site, exploring the maps, articles, and history, and discovered that two tile murals at my high school – one on the math building and one on the humanities wing – were also installed in the 1930s as Federal One Artist Projects (part of the second New Deal), and while they perhaps inspire less devotion from students than the gym does, they were created by local artists whose vocation was deemed valuable and worthy of protection and support by the Federal Government.

The Artists Project was one-fifth of the Federal One Arts Projects instituted by FDR in the second New Deal as an answer to creating jobs during the Great Depression. Even more interesting to me (for reasons) were the Writer’s Project and Historical Records Survey, in which unemployed writers, lawyers, librarians, and teachers were put to work on projects that used their interview, storytelling, and archival skills instead of sidewalk-building labor the WPA hired people for. The result was approximately 2,900 documents, compiled and transcribed by more than 300 writers from 24 states and currently housed at the Library of Congress as a collection called American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1940.

Included in that collection are the State and city guides that were the initial focus of the Writer’s Project, some of which were published, and continue to be updated and republished today. In the course of gathering local history for the guides, writers uncovered individual stories about people who met Billy the Kid, survived the 1871 Chicago Fire, and were coping with life during the Depression. Those interviews became the basis for more focused collections on American Folklore and narratives from the survivors of slavery – collections which have become the centerpiece of WPA works at the Library of Congress.

Critics of the Federal One Arts Projects were legion and began almost immediately calling for its dissolution. Artists, playwrights, writers, and musicians were “leftist communists” and supporting them with any kind of government sponsorship was dangerously un-American. Even the far left struggled with the Federal One Arts Project, arguing that State patronage would lead directly to State censorship of the artists and their art. I found a fascinating opinion piece on Artnet written by an art critic about the origins of the New Deal Arts Projects and the government’s role in their formation (in relation to the argument for supporting artists during COVID), which gives a detailed history into the protests, uprisings, and activism of artists and creatives during the 1930s. Apparently, a congressional committee even debated whether Christopher Marlowe (a contemporary of Shakespeare and contender for writing his plays) was a current member of the communist party as they argued to halt funding for the Theater Project.

There are so many facets to the Federal One Arts Project that intrigue me. I’ve written before about the small business support Margaret Thatcher instituted in the UK during the early 1980s which allowed artists and musicians to create some of the more avant garde works of that period while supporting themselves on thirty-five pounds a week from the government – an unintended liberal byproduct of a conservative economic rescue plan. The WPA Arts Project allowed Jackson Pollack to pursue his art instead of building sidewalks, but terminated Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko from the payroll for not being American citizens. There are recordings of Appalachian folk music and Black spirituals in the Federal Music Project archives that would have been lost to history without the sponsorship of the U.S. Government, and Zora Neale Hurston allegedly wrote her most famous book, Their Eyes Were Watching God in seven weeks while she put her anthropology degree to work interviewing formerly enslaved Floridians for the Slave Narratives project.

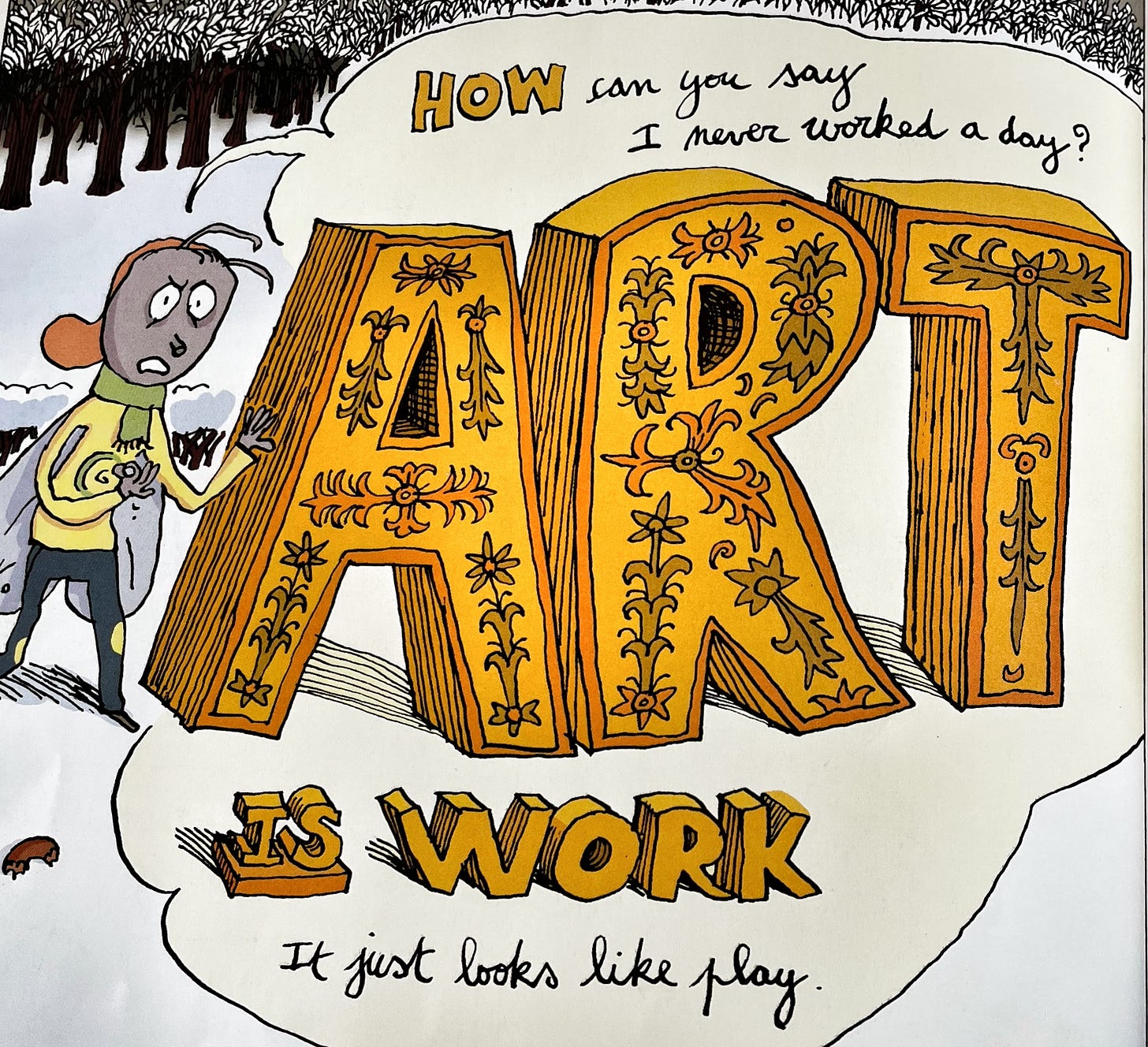

I haven’t read Their Eyes Were Watching God, but John Green calls it a brilliant American masterpiece with a complicated message. Another book with a complicated message about the value of supporting art echoes the fundamental message of the Federal One Arts Project. It’s a children’s picture book called Who’s Got Game, The Ant or the Grasshopper by Toni & Slade Morrison, and I read to my kids so often I can almost recite it from memory even now. The questions it asks have stayed with me all of these years, and it is perhaps one of the reasons I’m so intrigued by the idea of patronage for artists, whether private or federal: Of what value is art or music or literature when survival is on the line – as it was during the Great Depression, and as it is to some degree now? Can we truly call it survival if the cost is the sacrifice of art? And is the contribution of art to society reason enough to support the artist?

The economic future of this country is less certain now than even post-COVID, and funding for the arts seems to have been the first to go in the government “efficiency” sweeps. I read a story about the private music concerts and thinkers salons that gave hope to Ukrainians and kept the arts alive during the Soviet crackdown on “subversive” activities, and I know my own answer to the questions about the value of the arts to society. If the only thing we leave behind us is a story, telling that story where someone else can read it, hear it, see it, or recognize themselves in your words, your images, your music, or your movement – that is art, it is invaluable, and it is worthy of preservation, celebration, and support.